27 November 2013

Anybody who’s been reading this blog since my arrival in Paris knows that I have made it my goal to profit from my time in Paris and to see and do as many things as I possibly can while I’m living in what I consider to be one of the most amazing cities on earth. In order to make this project a bit more manageable, I have a list and, like Santa, I’ve been checking it twice to make sure that I get things covered. I also work hard to keep it updated with new sites and events as I learn about them. It’s getting a little tattered, but it’s still serving it’s purpose. In general this, combined with my random walks around Paris, have kept me very busy. I’m actually a bit surprised, myself, with how occupied my time has been and how tired I’ve been at the end of the day!

Unfortunately, my partner in Parisian Cultural Adventures works which means there are certain events and exhibitions that we can only do on weekends. One of these adventures was the Musée Jacquemart-Andre, which Ann Lawson and I visited last Saturday. Located in Paris’ wealthy and beautiful 8th Arrondissement, it’s only a short walk from the Arc de Triomphe and it’s really worth seeing. After meeting up at the Champs Elysées and walking down what is often called the World’s Most Beautiful Avenue, Ann Lawson and I began navigating our ways through the 8th to find the museum until we - well I - had a massive squirrel moment. As we crossed the street I happened to glance left and see the corner of a red building with a funny shape. I knew immediately what it was and I had to see it up close.

Called the Maison Loo, it is the Chinese Pagoda-styled house of art dealer Ching Tsai Loo, who arrived in Paris in 1902. Realizing that he would have much better luck selling his wares to the residents of the 8th arrondissement, Loo purchased an ordinary house that had been constructed in 1880 and opened shop. In 1926 the architect Fernand Bloch was engaged to do a bit of “spiffing up” to the ordinary building and, since building permits and codes didn’t exist at the time, Loo was able to really make it his own. Not surprisingly, the retrofitted Maison Loo caused quite a stink and despite a petition for its demolition, it remains today. Apparently the building was purchased in 2011 and is a private museum, am I am trying to figure out the details to see the interior, but the websites that I’ve found give plenty of conflicting information…

It doesn't exactly match its neighbors...

From the Maison Loo we were only a hop, skip, and jump from the Parc Monceau, a beautiful park that was once part of the private gardens of Phillippe d’Orléans, the Duc de Chartres and a cousin of Louis XVI. Today a public green space it retains some of the architectural features from its days as a private garden.

The Barrière de Chartres was designed by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and was constructed as part of the toll gates for the city of Paris in the 1780s. The first floor was the toll booth and the upper floors were reserved for the Duke's personal use.

Some of the Duke's garden follies

Having had a nice stroll, we decided it was time for sustenance; we found a nearby restaurant, and before long we were chowing down on our Norvegiens (see the last blog post for this).

By now it was getting late in the afternoon and we really had to get our fesses in gear so it was off to the Musée Jacquemart-André. Constructed between 1869 and 1875, and designed by Henri Parent, it was built as the bachelor pad of Édouard André, who was 42 at the time of the its completion. An avid collector, André had already amassed a very impressive collection and he installed it into his house. Six years later he married Nélie Jacquemart and together they spent the rest of their lives collecting together (Édouard died in 1894 and Nélie in 1912). On December 8th, 1913 the Musée Jacquemart-Andre was opened to the public and now, almost a century to the day later, this house provides an intimate view into the lives of these two patrons of the arts and their life together in Paris. Although this is only a very tiny portion of the total photos, I think it provides a pretty good view of the museum, its collections, and the lifestyle of Monsieur et Madame André. Even though this museum isn’t one of the “big” museums of Paris, it’s really worth visiting. It’s just incredible!

Unfortunately the building is currently hidden behind scaffolding so here's a better photo that I found on Wikipedia. You actually enter at the very far left (in your carriage of course) and go up a curving ramp and then turn in (well your driver turns in) toward the main house to drop you off at the front door. Then he drives out on a similar ramp on the right. It's really a fairly elaborate entrance procedure, but I'm sure I could get used to it.

As you walk into the house the first thing you notice is the use of gold. Everywhere!!!

This room was especially interesting because the entire middle section of the wall that is pictured here, between the two columns, can be lowered into the floor to make one - very large - room.

If you click on this photo to enlarge it, and look above the panelling, you can actually see the section that isn't attached to the ceiling and allows the wall to drop into the floor. How cool is that?!

A sitting room.

And another.

And a really beautiful commode from 1720.

The ceiling of the music room.

The staircase is symmetrical and clearly shows how Henri Parent, the architect, was still a bit sour over the fact that he had lost the competition of the Paris Opera House. Sure Garnier's staircase at the Opera is a bit more grand, but this is still pretty impressive!

Off the stair hall is the glass room for the plants and the smoking room (which was actually behind my back as I took this photo)

Looking down onto the first floor stair landing from above.

Above the staircase is this fresco painted by Giambattista Tiepolo for the Contrarini Villa in the Veneto from about 1745. It was purchased but the Andrés (who adored Venetian art) in 1893. Notice how the stone work at the right side is actually altered so the leg and foot of one figure can hang below the rest! The fresco shows the arrival of Henri III to Venice being received but the Doge as he was headed to Paris to succeed his brother, Charles X as king.

Following the death of M. André, his widow continued collecting and ended up furnishing some of the second floor rooms that had been untouched.

Back on the ground floor in the breakfast/sitting room between the bedrooms of M. and Mme. André. Their portraits are on the wall.

Monsieur Andrés bedroom, remodeled by his widow following his death.

His bathroom.

The current special exhibition explores the Désires and Volupté of Victorian era painting. These paintings both depict fairly desirable subjects, if you ask me.

On Sunday, I decided to be a martyr, humor Ann Lawson, and go to the Dior show at the Grand Palais. Imagine my incredible disappointment when we found out that the line to get inside would take 3 hours… shucks…. well what to do, what to do!? Eat of course, but then what? Well as we were leaving the restaurant on Saturday we happened to walk by (and even walk into the courtyard of) another museum that was on my list: the Musée Nissam de Camondo, but we decided to the do the Jacquemart-Andrew instead. Well today was the day for the Camondo! Like the Musée Jacquemart-Andre, the Musée Nissam de Camondo was another house museum, where everything remained exactly as it was when the family was in residence. The only difference in this case was the fact that the Camondos were a Sephardic Jewish family who made their money in the banking industry and had very specific interests.

Nissam Camondo (1830-1889) came to Paris with his brother and worked to increased the family’s fortunes under the rule of Napoléon III. In 1910 his son, Compte Moïse de Camondo (1860-1835) inherited his parents’ property and decided to have the house torn down and replaced with a structure in which he could show the collection he had amassed of art and furniture largely related to 18th century France. Using the architect René Sergent, a new structure was built, somewhat similar in style to the Petit Trianon at Versailles, the house of Louis XV’s mistress the Madame de Pompadour.

Moïse had a collection that ranged from art to furniture to china and silver, even entire room interiors that had been removed from 18th century buildings! He had it all. In order to display his treasures he created a house for modern living (the house wasn’t completed until 1912) using the 18th century pieces that he had collected.

Unfortunately, the son to whom Moïse intended to will his entire collection, Nissam, was killed in World War I. So, trying to make the best of the situation, Moïse decided to make his house and its contents a museum following his death, named after his late son. Inaugurated on December 21, 1936, almost nothing has changed since Moïse died in 1935. On a more somber note, however, Nissam was not an only child. He had a sister named Béatrice who lived with her husband and their first child for a period of time in the house of her father before they moved to their own house and had a second child. Unfortunately, Béatrice, Léon, and their two children, Fanny (born in 1920) and Bertrand (born in 1923), we all deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz where they died. Today the only remnants of this family are in this museum but they create an incredible memorial to the Camondo family. It’s hard to say which museum I preferred, the Camondo or the André. Both feature impressive collections and there were moments in both when I was absolutely speechless and awestruck. In the end however, I think the Musée Nissam de Camondo would win because you got to see the entire house, even the service areas, which were really impressive. You’ll see why when you look at the photos.

I love the panoramic feature on my iPhone. It may distort the image a bit, but you really get to see the entire space.

Central portion of the museum

The Petite Trianon at Versailles

Ground floor looking toward the front door behind the staircase

Walking up the staircase you start to understand that this house was built to showcase the Moïse Camondo's collection. Look at how perfectly this Japanese lacquered panel corner cabinet (c.1750 attributed to Bernard Van Risen Berg) fits in with the bannister. As soon as Ann Lawson and I saw this we both knew that this was a man who really loved his collection and wanted it to look its best.

The first room as you go to the top of the staircase. The "Upper Ground Floor" was where all of the public rooms were placed. This photo and the next two are from the Great Study. The tapestries are c. 1775-1780 by the Aubusson manufactory and show the Fables of LaFontaine.

I found these two chairs, which are called "voyeuses" especially interesting. They are made so you can kneel at a table and play cards. They were are from 1789.

Ann Lawson looks at Baccante, 1785, by Elisabeth Vigée Lebrun

The Great Drawing room features panelling that came from a house on the rue Royale and dates to 1782-85. The carpet, which dates to 1678, was made for the Grande Gallerie of the Louvre back when it was still a royal residence.

Portrait of Geneviève-Sophie Le Couteux du Molay by Elisabeth Vigée Lebrun, 1788,

Salon des Huet, named for the paintings by Huet (1745-1811) which are set into the paneling. The carpet dates to about 1740 and if you look at the center you can see where the 3 fleur de lys, the symbol of the French monarchy, were removed following the Revolution.

Dining Room

The small study. The table at the center, a chiffonière, was constructed for the private apartments of Marie Antoinette at Versailles and was meant to hold her current needlework project.

Some of the paintings, mostly third quarter of the 18th century.

The blue drawing room, which replaced the apartments of Béatrice de Camondo in 1923.

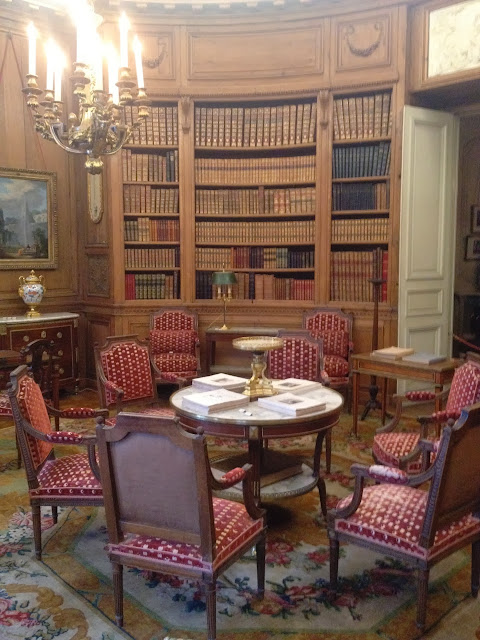

The library

The ceiling of M. Camondo's dressing room, which was copied from a design by the Scottish architect Robert Adam.

This was the bedroom of Nissam de Camondo with a portrait of his grandfather over the bed.

The bathroom tiles in the master bathroom. Here is one of the areas where you can really see that this house was modern, finished in 1912.

The other bathroom had equally beautiful tile work.

This is the "roasting range" in the kitchen, which was coal fired. As installed, the heat of the fires would turn a fan in the top of the range, in the part called the smoke jack, which would, in turn, rotate the rotisseries.

The kitchen is directly below the dining room but is built completely of concrete and is tiled to ensure that no sounds or smells get into the rest of the house.

The range, which dates to the original construction (1912). Interestingly, the smoke actually goes out through a chimney in the floor and the dampers are controlled by the levers on the wall, which can be seen in the corner.

The servant's dining room.

The final museum of the trio this week was yet another house museum. Unlike the first two however, this house was not of a largely-unknown family. It was the house of a very important man: the one, the only Victor Hugo. Author of Notre Dame de Paris (better known as the Hunchback of Notre Dame), Les Miserables, many books of poetry, and (unknown to me before my visit) a fairly prolific artist in his own right, Hugo lived in many places throughout Paris, including one of my favorite spots: the Place des Vosges.

Started under the reign of Louis XIII and finished under his son, the Sun King, Louis XIV, the Place des Vosges was originally called the Place Royale and in one of its brick and limestone buildings Hugo lived from 1832-1848. Today his apartment is home to the Musée Victor Hugo, a strange collection of artifacts from his life. Personally, I was very excited to see the interior of one of the Place des Vosges buildings in addition to learning more about a French author about whom I knew very little. Unfortunately, this building has been heavily altered inside and little remains of the layout that existed during Hugo’s time. In fact, according to the information that I read in the museum, they still aren’t exactly sure how some of the rooms were laid out or used which makes it difficult. Furthermore, almost none of the original decoration remains… I could go on, but I’ll stop here.

At the time of his death Hugo’s widow was obliged to sell some of her late husband’s collection and a particularly avid fan of the author purchased many of the items. It was that purchase that formed the basis of the Victor Hugo Museum and it is probably for that reason that the museum seems more like a memorial homage to the writer by than a true museum; at the basis it’s just the collection of a fan. I have to say that I didn’t leave feeling as though I’d really learned anything. Instead I felt as though I left a space that was filled with things that had a connection to an individual but really didn’t play a part in his life. For example. Just because Hugo’s father had two leather traveling cases, one from 1680 and one from 1731, doesn’t make or mean anything in the world of Victor Hugo’s career as an author. Or of his life. It just is. His dad had 2 traveling trucks that still survive today. Cool, sure. Relevance? Meh.… In any event, they’re on display.

The one thing for which I will give credit to the Hugo museum is their price: it’s free. All I had to pay for was an audio guide. As I was leaving and feeling a bit bummed out about the museum at least I knew that I had only spent 5 euros on the experience and spent 45 minutes there. (Without the audio guide I’m sure it wouldn’t have taken any more than 20 minutes to see the entire museum.)

Place des Vosges from the central square

Looking toward Victor Hugo's house (the righthand building at the corner)

Under the arcades

The Victor Hugo house. His apartment was on the third floor.

The staircase

Victor Hugo and his son, Victor, but Auguste de Châtillon, 1836

Quasimodo saving Esmerelda by Mlle Henri, 1832

I loved looking out the windows and seeing the Place des Vosges. The views made up for the mediocre museum.

Apparently he decorated the house of his mistress in the Chinese style. Today pieces of the Chinese decor, now removed and installed in a very strange manner, are shown in the museum. The center thing, with the red, was once a fireplace surround (notice his initials on the sides). Unfortunately the original layout was destroyed when they took the pieces and arranged them here. Some of the panels were interior shutters, some where small panels that were cut, and it's just bizarre. But I think it's really interesting to know that Victor Hugo was an interior decorator as well.

At least he had a healthy ego, even when decoration his mistress' house.

See the initials?

A reconstruction of his "English" dining room

Victor Hugo's writing desk. Apparently he preferred to write standing up

Victor Hugo's death bed.

On my way home I met up with a friend for coffee and then walked home from the café, passing one of my favorite buildings in Paris, Les Invalides. Now known as the home of Napléon’s tomb, it is also a military hospital and was likely originally conceived as the burial mausoleum of the Bourbon family (a little tidbit I learned as a student at SciecesPo). Today there was some sort of ceremony going on outside near a monument to men lost at war, so I stopped to enjoy the beautiful sunset, try to figure out what was going on, and imbibe myself of some more French culture.

My first video on the blog. It's sort of grainy I had to reduce the quality the file small enough for the blog. You can use the full screen option, which isn't terrible. Anyway... does it get any better than being in front of Les Invalides, the Eiffel Tower dominating the skyline to my left, with a military band playing La Marseillaise, the French National Anthem? I think not.

No comments:

Post a Comment